Signs of recovery are appearing among previously overfished large-bodied fish stocks. This is good news, but may also present new challenges.

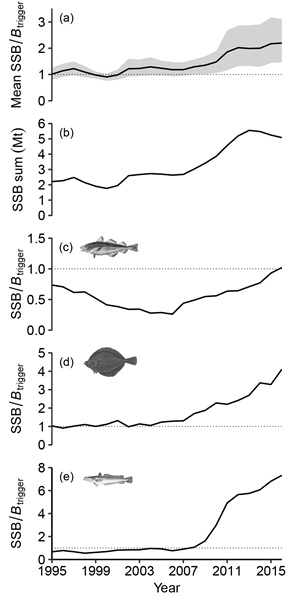

We are seeing an increase in stocks of large-bodied fish species in the Northeast Atlantic, including the North Sea. Researchers from DTU Aqua have analysed data for the fish species that can reach a maximum size of at least one metre, and the figures show a large increase—both for these species summed-up, and for selected species such as cod, plaice and hake. The data comes from the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES).

“Stocks of large-bodied fish, like cod, have been under pressure for some time. But now we are finally seeing signs of recovery,” explains PhD student Rob van Gemert, who is the main author behind the study which has just been published in the ICES Journal of Marine Science.

Based on data up to 2016, the study shows more than a 100 per cent increase in stock biomass for the 25 examined species of large-bodied fish since the year 2000.

For cod, plaice, and hake in the North Sea, we are seeing threefold and sometimes fourfold increases up to 2016. Even though the stocks increase on average there are also declines. One example is the data from 2017—which was not included in the data time series used for this study—where a decrease in biomass for cod is evident.

The study also shows that while a number of species were previously close to collapse due to overfishing, stocks have now recovered sufficiently for fishing to resume based on the Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) reference point without further restrictions. For some species—like plaice and hake—this point has already been exceeded. For other species, it is close.

Maybe fish stocks need thinning

For decades, the large-bodied fish were few and far between. Significant efforts have been made to restore these stocks by setting quotas according to the levels recommended by ICES, by setting fishing effort limitations, by implementing new technical measures such as increased mesh-size in the fishing gears, and by establishing closed areas. All based on knowledge gained in cooperation between researchers, fishermen, and authorities.

However, a situation where stocks seem to have recovered may come to present new challenges for fisheries management: Increased competition for food between the large-bodied fish.

“There will be many more of large-bodied fish, and they all have to eat. Once numbers have reached a certain level, the fish start competing with each other for food, and some will not get enough to eat, slowing growth rates. This is not something which we have been aware of before, simply because these stocks have been close to depletion for as long as we have been collecting data about them,” says Rob van Gemert.

He compares it to thinning carrot seedlings in one’s vegetable garden to give the remaining carrots enough room to grow.

The illustration shows the development in average biomass for the 25 large-bodied fish species examined as well as developments for cod, plaice, and hake. The broken line shows the level of biomass defined by ICES in 2016 as the minimum level of biomass necessary for fishing to take place based on Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY). Data from 2017 is not included in the study.

Many large-bodied fish means fewer small fish—and vice versa.

When large-bodied fish become more abundant, stocks of small-bodied species—their prey—will, of course, decrease. This goes, for example, for herring and sprat. In the study, the researchers therefore also describe the possible consequences for both fish and other animals in the food chain:

“We call it a reverse trophic cascade. An increased predator biomass leads to lower prey biomass, which impacts the productivity of the prey fish. Ultimately, this will impact the fishermen who catch the small-bodied fish, such as sand eel and sprat,” he says.

The research is part of the MARmaED project, which is funded by the EU’s Horizon 2020 research programme.