Center for Electron Nanoscopy—

DTU Cen—is celebrating its tenth anniversary on 7 December. We are marking the event with three stories about the centre’s important role for DTU’s research.

On 7 December 2007, the Centre for Electron Nanoscopy—commonly referred to as DTU Cen—opened its doors for the first time. A donation from the A.P. Møller Foundation made it possible to procure eight high calibre electron microscopes and install them in a special temperature-controlled environment where resonance and vibrations are kept to a minimum.

Since then, the centre has established itself as a central facility used by researchers and students from the majority of DTU’s departments, several Danish and international research institutions, and industrial enterprises.

The instruments, which can examine both hard and soft materials of all kinds in great detail, are in use nine hours a day all year round. Electron microscopy has become an important part of many researchers’ everyday lives—we spoke to three of them.

Much more than a technology centre

Cathrine Frandsen is a professor at DTU Physics. Among other things, her work focuses on magnetic nanoparticles.

“Before DTU Cen, there was just one old microscope at DTU and perhaps one or two who could use it, but with Cen we got some of the world’s best microscopes and expert instruction on how to use them.

As a postdoc, I had travelled to the USA to learn how to use electron microscopes, so it was amazing for me that we got something similar in Denmark. The centre’s first director—Rafal E. Dunin-Borkowski—was a world-leading authority on magnetic materials and managed to attract several highly qualified staff in the field.

It has been crucial to my research that I was able to enter into a research discussion with them from the outset. Cen researchers are involved in all phases of the projects—namely start-up, performance, and analysis. It’s really exciting.

I can’t imagine DTU without electron microscope facilities and I’m delighted that there are plans to develop and expand the centre.”

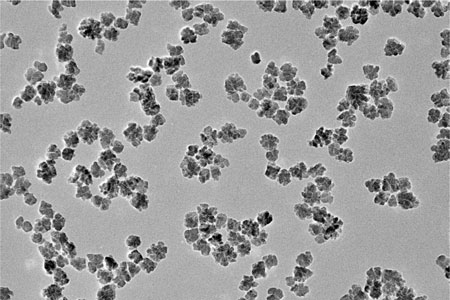

Nanoflowers

Cathrine Frandsen is experimenting building new magnetic materials with new properties by clumping nanoparticles together. The clumps of particles called nanoflowers become warm when connected to an interacting magnetic field—a phenomenon that may have applications in cancer treatment.

Photo: Cathrine Frandsen

Superb family photos

Lone Gram is a professor at DTU Bioengineering and her field of research is bacteria. In brief, her goal is to destroy bad bacteria and exploit good ones.

“It’s extremely valuable for me and my research group to get ‘family photos’—i.e. good high-resolution images of our bacteria. For example, when describing a new bacterial species, we are expected to provide good microscope images of the organism.

We’re also interested in antibiotic substances and how they function—and together with DTU Cen—we’ve been able to visualize the effect of these substances on the bacteria’s cell surface. This is incredibly useful, both in terms of documenting research and showing that you’re developing non-problematic methods and substances.

Over the years, Cen has become increasingly relevant in the field of bioscience and researchers have begun working with electron microscope procedures where cells don’t need to be fixed but can be studied in wet systems—giving a better picture of their appearance and how they interact.

I never actually set foot inside the Cen building before coming down here to be photographed. Together with the centre’s employees, we prepare procedures for cultivation and harvesting bacteria, and the remaining part of the analysis work is carried out by Cen. I have a biological goal, and the centre helps me to reach it with the help of electron microscopic analysis. That’s the great thing about Cen.”

Marine bacteria

Scanning Electron microscopy of the marine bacterium Phaeobacter piscinae. The bacteria are spawned in rosettes—as opposed to single cells. The rosette formation may be a way to avoid being eaten by larger organisms. Photo: Lone Gram.

Without Cen, we would be unable to publish

Anders Baun, professor at DTU Environment, researches into whether nanoparticles have an undesirable effect on the environment.

“Electron Microscopy is a very important tool for us. At DTU Environment, we have many activities within the nano field, but we’ve decided not to invest in our own microscopes. We would rather use Cen and their excellent staff.

It’s important for us to see how the nanoparticles organize themselves and what happens to them when they are absorbed by a living organism. ‘Seeing is believing!’ But it’s worth remembering that even if you find a man holding a weapon at the murder scene, you can’t be sure he’s the killer. The same principle applies to our research. We use many different methods to achieve our results—the electron microscope is just one of several instruments we use in our experiments.

That said, without the electron microscope, we would have great difficulty getting the scientific journals to accept our articles. It is an accepted standard of good scientific journals that findings must be supported by electron microscopy. The same holds true for research applications—and being able to write Cen lends credibility and street credit to our applications.

We don’t use the most sophisticated instruments at Cen. We simply need to document that our samples contain nanoparticles—where they are and whether they have clumped together. But you can’t put biological samples in the microscope as they are. They must first be treated, and by so doing, you may destroy them. It would therefore be interesting for us if the instruments had cryo-electron capability so that we could view the samples in their frozen state. It wouldn’t save time, but it might provide better results.”

Risk assessment

Microscopic image of of an adult flea—one of the aquatic organisms used in the risk assessment of chemicals and nanoparticles. The researchers examine whether the particles simply pass through the gastrointestinal system—or whether they are absorbed by the organism. Photo: Anders Baun.