Two engineers from DTU are helping conservation bodies in the Nordic countries to restore the flashing, sweeping lights of preservation-worthy lighthouses.

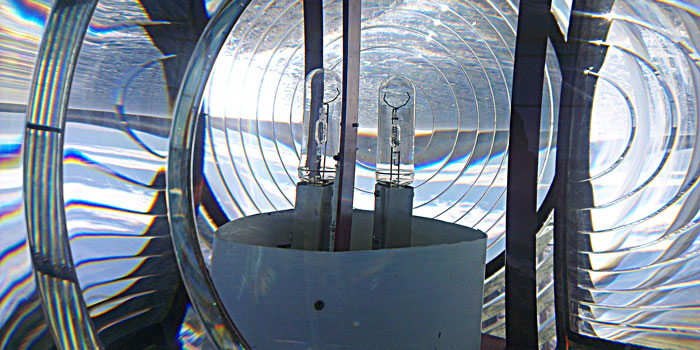

A real lighthouse is distinguishable by its sweeping beam of light. That has certainly been the case since the 1800s, when lighthouses featured a huge lens in a bath of mercury that revolved around the light source—initially a paraffin lamp—and subsequently a powerful electric light bulb.

But during the earthquake in 2008, Nakkehoved lighthouse in Gilleleje, Denmark, wobbled so much that some of the 30 litres of mercury leaked out. Naturally, this resulted in an order from the environmental authorities to remove the old mercury in its entirety. And so it was that bulbs and rotating lenses were replaced by a rod with lots of LED lights that flashed alternately—much to the regret of both museum staff and local residents, who felt that the sweeping lighthouse beam was an integral part of Gilleleje’s soul.

“When they got rid of the lighthouse keepers, they forgot that they actually performed a lot of maintenance work,” says Peder.

When the rumour spread that the Nakkehoved lighthouse’s sweeping light had been saved, the two DTU engineers received several inquiries, and to date, they have ‘saved’ three other lighthouses in Denmark, one on the Faroe Islands, two in Sweden, and seven in Norway from the sad fate of LED lights. However, their work has never become routine, as no two lighthouses are the same—despite the fact that they were all built by the same Parisian firm between 1854 and 1906. Peder and Niels simply have to visit each site and adapt their solution to the individual lighthouse. Each job takes roughly 100 hours.

“It's scientific advice with a cultural aim. The lights no longer have any practical significance for shipping, as navigation is now handled via satellite,” says Peder Klit.