Sustainable travel

Two engineers, a colour researcher, and an innkeeper stuck on a train

Two DTU researchers’ attempt to get to a climate conference in France with the least possible carbon emissions leads them on a long and complicated tour of Europe. The question is, would they do it again?

Who flies to a climate conference?

It was Isaac who had come up with the idea of taking the train instead of flying. Six months ago, he sent an email to his colleagues at DTU Chemical Engineering, asking the following: “Hi all. I plan to take the train to the climate conference in Lyon. Who wants to come?”. In fact, Isaac tried not to attend conferences where you have to fly to get there, in accordance with DTU’s guidelines for staff to reduce their air travel.

Jens was the only one from the department who responded to Isaac’s email. He tapped Isaac on the shoulder in the corridor in the Center for Energy Resources Engineering (CERE) and said: “I would like to come.”

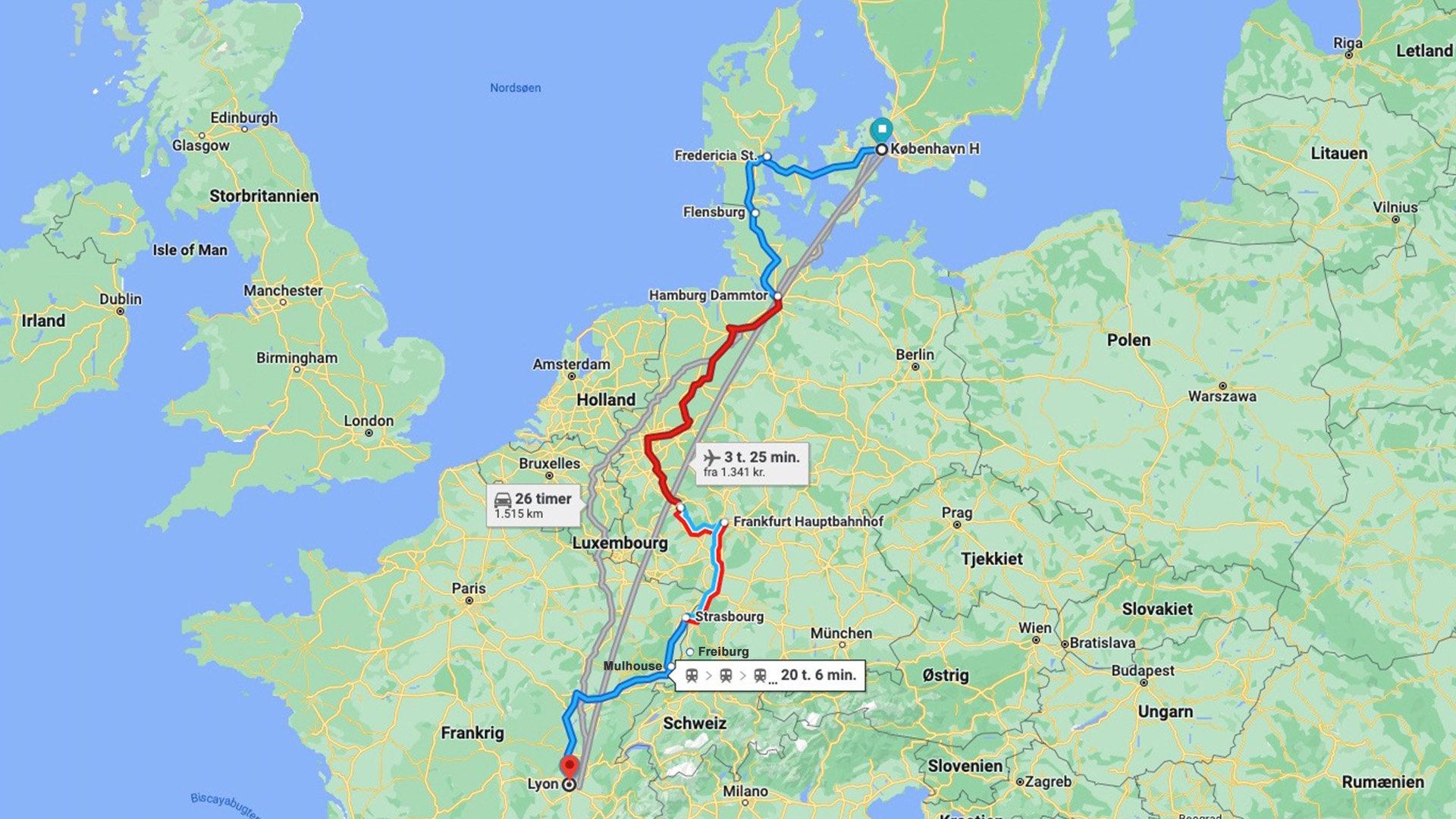

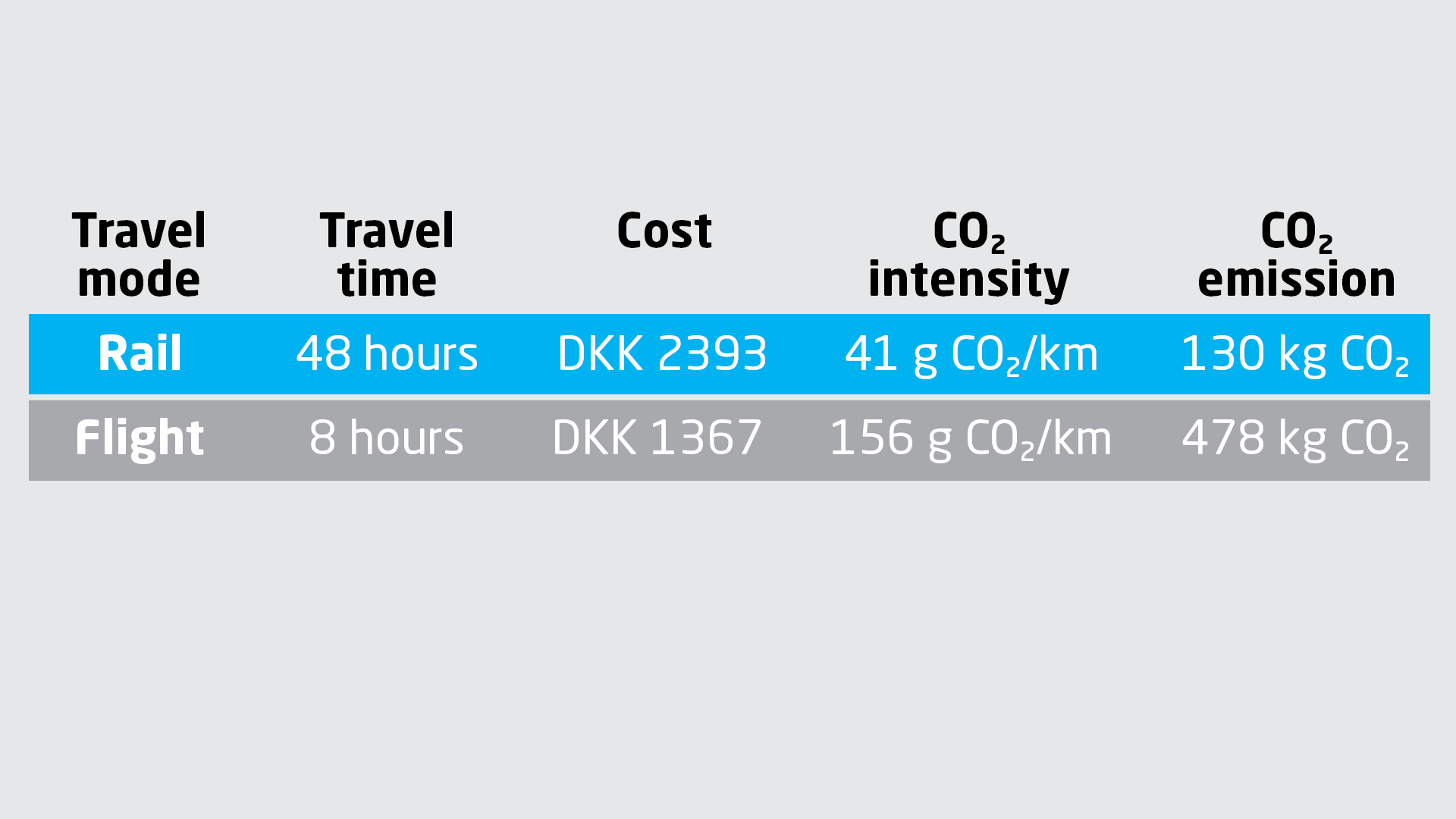

Jens thought it sounded like a good idea to take the train, not least because of the signal value. That is, why fly to a climate conference? The train was not the most natural choice for Jens, who typically thought with his wallet in relation to transport. A train journey to Lyon would take much longer and cost more than a flight. To be precise, it would take six times longer and cost just over DKK 1.000 more. Nevertheless, Jens found it difficult to argue in favour of a mode of transport that was estimated to emit about four times more CO2 than a train journey. Therefore, he jumped on the wagon.

The trip went south

Back at the busy Hamburg Central Station, Jens fell hungry. Jens—whose day-to-day work involves biogas carbon capture—had been on a train since a quarter to seven in the morning, and it was now 1 p.m. Isaac agreed to find something to eat while they waited.

They bought some bread, chocolate biscuits, water, soft drinks, and a six-pack of beer for the rest of the trip from a supermarket nearby. If something happened, they would at least have something to drink and eat.

On board the train, Isaac and Jens’ plan to catch a connecting train in Karlsruhe was derailed after just 45 minutes. Another announcement from the speakers: “We’re experiencing ‘störung’ and are waiting for a signal that we can continue.” Isaac and Jens could not help but laugh out loud because now they could wave goodbye to their planned overnight stay and dinner in Strasbourg.

In order to have maximum flexibility during their train journey, Isaac and Jens had bought Interrail tickets without seat reservations. This meant that they could not be sure of getting a seat. On the stretch between Hamburg and Karlsruhe—where the delay lasted for over an hour—Jens and Isaac therefore found themselves sitting half a carriage's distance apart. Instead of talking, they communicated via Facebook Messenger, where they shared screenshots of alternative itineraries.

This is how they brainstormed their further journey separately until Jens went to where Isaac was sitting, squeezed into one seat, and said: “Where do we go from here?”.

Executed plan C

While Isaac and Jens sat buttock to buttock in the same seat pondering what to do, the train was further delayed. It was 7 p.m. when Jens aired the idea that they should just stay on the train instead of getting off in Karlsruhe. “Let’s go to Basel in Switzerland,” Jens suggested as plan C, which entailed getting as far south as possible. “Fine,” said Isaac. He was pretty tired. As the train drove past Karlsruhe, they managed to find two seats next to each other.

In their new seats, Isaac and Jens struck up a conversation with a Danish mother and her daughter who were headed for Zurich in Switzerland. The mother worked at different restaurants in Switzerland—as a kind of innkeeper—up in the mountains. She preferred taking the train, with only one change en route. She felt that the train provided time for reflection, and enjoyed the time it gave her with her daughter.

Please leave the train

As the train rolled into Freiburg Station, 70 km north of Basel, the train conductor said over the loudspeaker: “This train will stop here.” The train passengers were informed that they could instead take another train from the opposite side of the platform that would depart “as soon as possible”.

The two engineers boarded the replacement train and found new seats next to a Danish retired colour researcher from the Glyptoteket museum.

The time was 10 p.m. Three hours later than the time when Isaac and Jens had expected to be sitting in a restaurant in Strasbourg eating quiche lorraine—an egg and bacon pie—for which the city is famous. Instead, their dinner consisted of chocolate biscuits. Their last supplies from the supermarket in Hamburg.

While Isaac and Jens waited for the new train to continue from Freiburg Station, the colour researcher showed them videos of his work with classical sculptures at Glyptoket. Both the colour researcher and the engineers were enthusiastic about each other’s work and the conversation developed into an open invitation for Isaac and Jens to visit Glyptoteket for a tour.

When the conductor assured the passengers for the sixth time that the train would depart shortly, Isaac began to walk up and down the aisles of the train. He did cartwheels and handstands on the platform next to passengers who had descended the train to smoke.

Late arrival in Basel

The train did not move an inch for two and a half hours. Meanwhile, Jens and Isaac had time to discuss different plans. For example, they could get off the train in Freiburg and spend the night with some of their acquaintances. But they would then not be able to arrive in time for the conference in Lyon at 3 p.m. the next day. Or they could take a Flixbus from Freiburg at 3 a.m., which could take them all the way to Lyon. But they would then have to sleep on the bus.

Half past midnight, the train left Freiburg station and Isaac was finally able to calm down and close his eyes. When Isaac woke up again, they found a hotel room online in Basel SBB, the stop after Basel Bad. But when the train reached Basel Bad, it stopped and did not proceed. This was equivalent to being thrown off the regional train at Høje Taastrup Station instead of Copenhagen Central Station.

In Basel Bad, they took the first available tram, which fortunately took them straight to Basel SBB, a 5-minute walk from the IBIS budget hotel, where they got 3-4 hours of sleep.

The morning in Basel offered street musicians, freshly baked sandwiches, and coffee before they headed first towards Mulhouse and then Lyon. They managed this in just three and a half hours. They reached Lyon at the same time as they had planned from the start, i.e. at 1 p.m., so the journey time itself had not been longer despite a seven and a half hours’ delay.

Saved two months of emissions

According to the Ministry of Climate, Energy and Utilities, each Danish citizen emits approx. 11 tonnes of CO2 per year through their consumption of, for example, travel. At the same time, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assesses that if global warming is to be limited to below two degrees Celsius, we must globally reduce our emission to the equivalent of approx. two tonnes of CO2 per world citizen in 2050. It is thus clear that the current Danish lifestyle is unsustainable.

According to their own calculations, Isaac and Jens saved the climate 350 kg of CO2 per person by taking the train instead of the plane. This corresponds to a reduction of two months’ emissions out of a total annual quota of two tonnes of CO2.

For Isaac and Jens, climate-friendly consumption is about being conscious of the impact on the climate, just like many of us are when bargain hunting in the supermarket. But this requires knowledge about the climate impact of the goods—or in the case of Isaac and Jens—of the transport.

For Isaac and Jens, the train journey did not go quite as planned, but, at the same time, they had not foreseen the sense of fellowship and togetherness that arose along the way with the woman innkeeper and the color researcher, which made the waiting time unique. The trip had also brought them closer together as colleagues, because they had now learned how short or long the other’s fuse was. Would they make the trip again? Yes, definitely! Next time with more than a half hour of changeover time.

Contact

Isaac Appelquist Løge Postdoc Department of Chemical and Biochemical Engineering Mobile: +45 53141399 isacl@kt.dtu.dk

Jens Kristian Jørsboe Student Students s140280@student.dtu.dk